On Tuesday 15th of January, WeChat blocked 3 competing Apps on their launch day: Liantianbao (聊天宝) – formerly called Bullet Messenger, Duoshan (多闪) – launched by Tencent’s archenemy ByteDance, and Matong MT (马桶MT) – launched by Ringo.AI.

Is this approach to competition specific to WeChat? To the Chinese market? And how do Chinese and Western companies differ in their growth strategies?

Building companies versus building ecosystems

Chinese and Western companies tend to have a dramatically different approach to expansion. In a few words: Western companies build products, while Chinese companies build ecosystems.

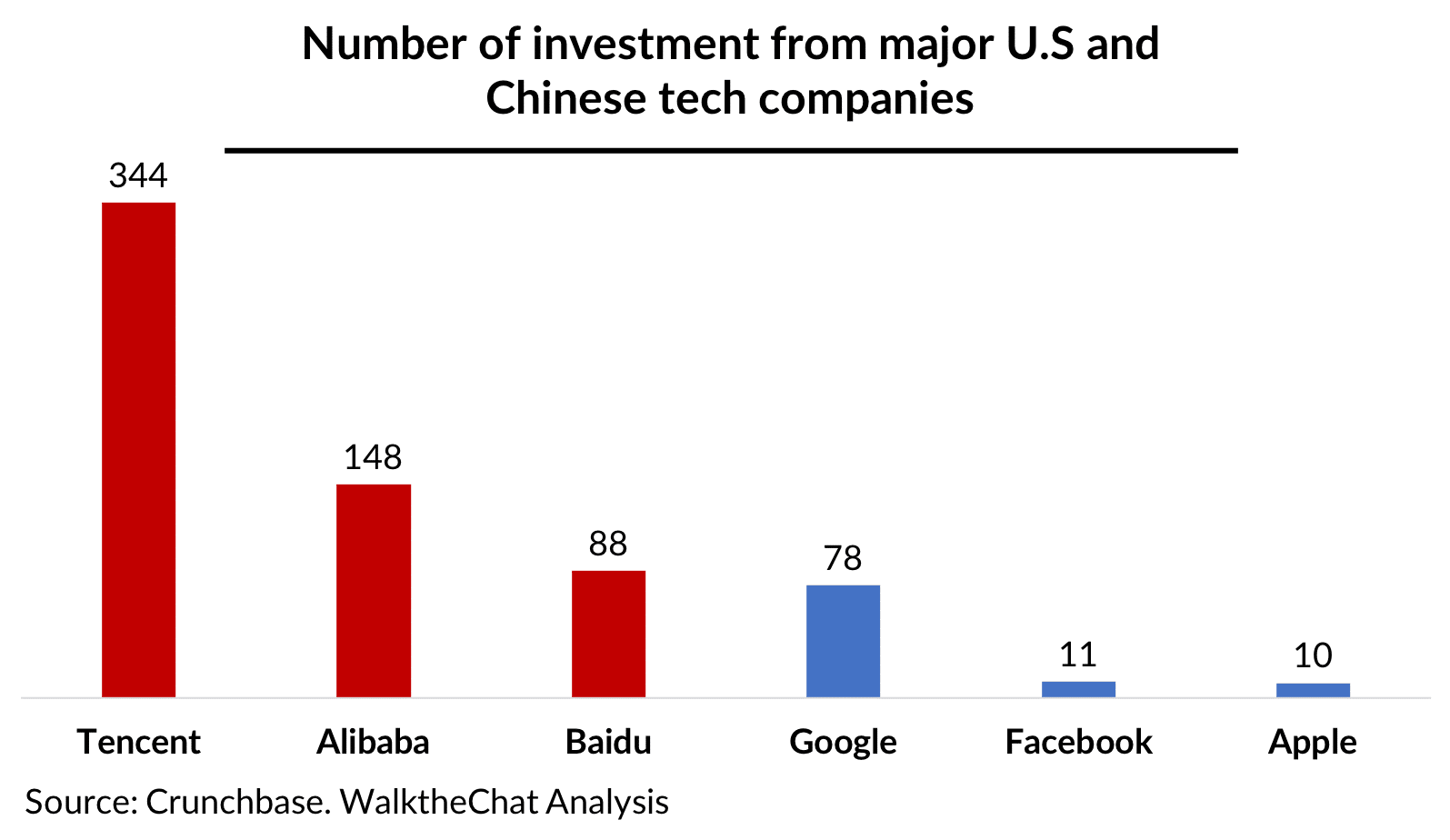

Nowhere is this trend more obvious than in the investment pattern of Chinese and Western companies. Chinese companies tend to be much more active early-stage investors into booming companies.

The purpose of these investments is to build a system of allegiance to the group. After receiving investment, the company will have to ingrate with the ecosystem of the group and reject the competing ecosystem.

As a consequence, Pinduoduo heavily integrates with WeChat and offers WeChat Pay as a recommended payment method, while JD.com doesn’t support Alipay altogether. Both companies of course received investment from Tencent.

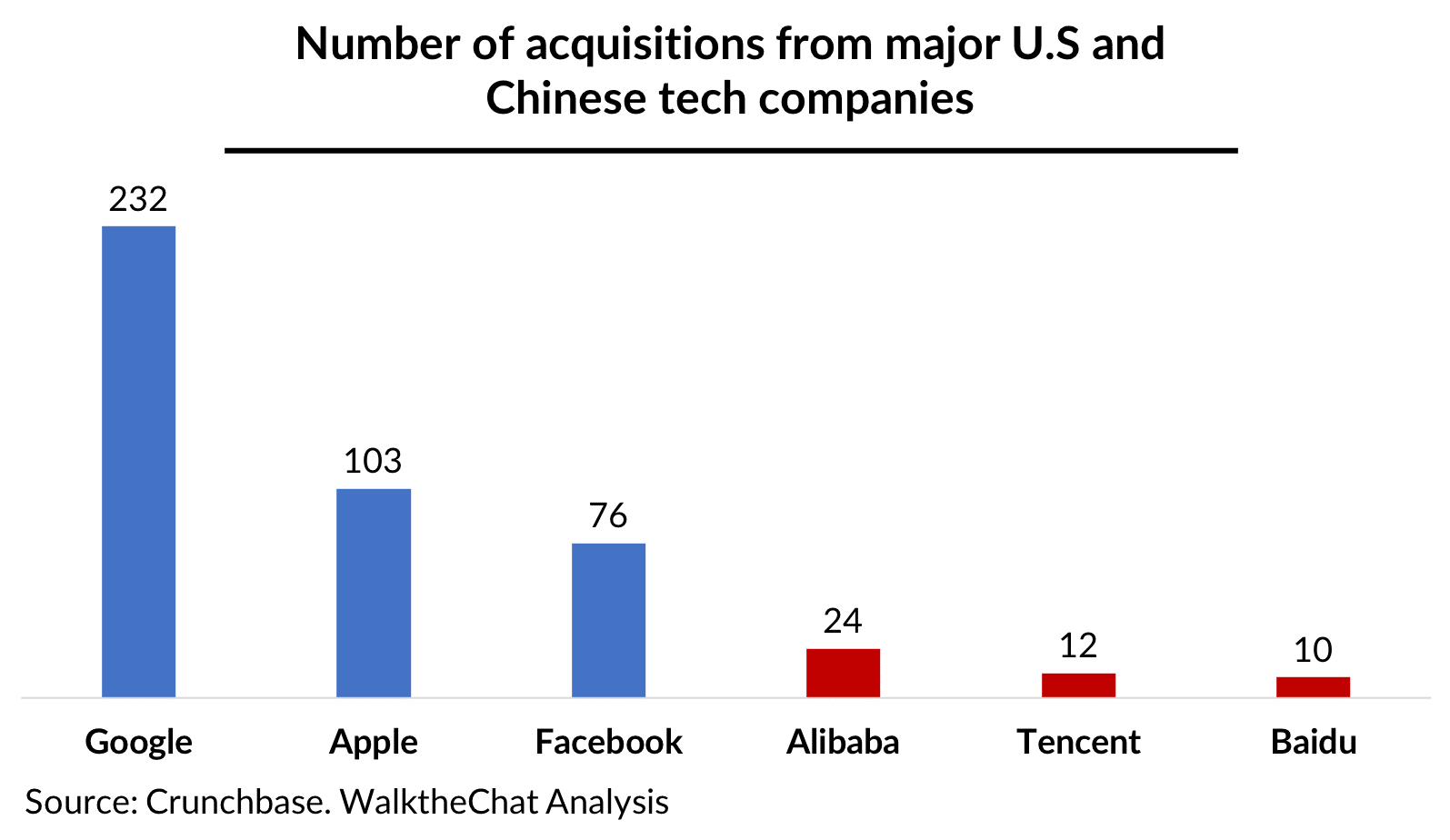

Western companies have very different expansion pattern: they tend to rely on acquisitions instead of investments.

These acquisitions can constitute major operations aimed at overtaking superstar products (such as Facebook acquisition of WhatsApp, Instagram and Oculus Rift or Apple acquisition of Shazam last September).

But more often than not, these acquisitions are technology or acqui-hiring operations aimed at developing existing products, such as the acquisition of Redkix by Facebook in July 2018 (which was merged with Workplace by Facebook) or the purchase of Senosis by Google in September 2018 (which was merged with Nest Lab).

Guerrillas and castles

The approach of Western tech companies to competitive warfare is akin to protecting a castle: they have a defined territory and will relentlessly protect it if the adversary gets close enough. Their acquisition strategy is meant to build stronger defenses against their enemy. But they will likely stick to this territory and make limited foray outside of their core domain of expertise.

Chinese tech approach to competition is more similar to guerrilla warfare: fights happen everywhere, all the time, between a large number of stakeholders both big and small.

As such, foreign companies tend to be much more permissive toward other tech players leveraging their tools. For instance, there is no problem for a Facebook post to link toward an Amazon link, and Google will of course direct you to a relevant Facebook profile.

How WeChat and Alibaba approach competition

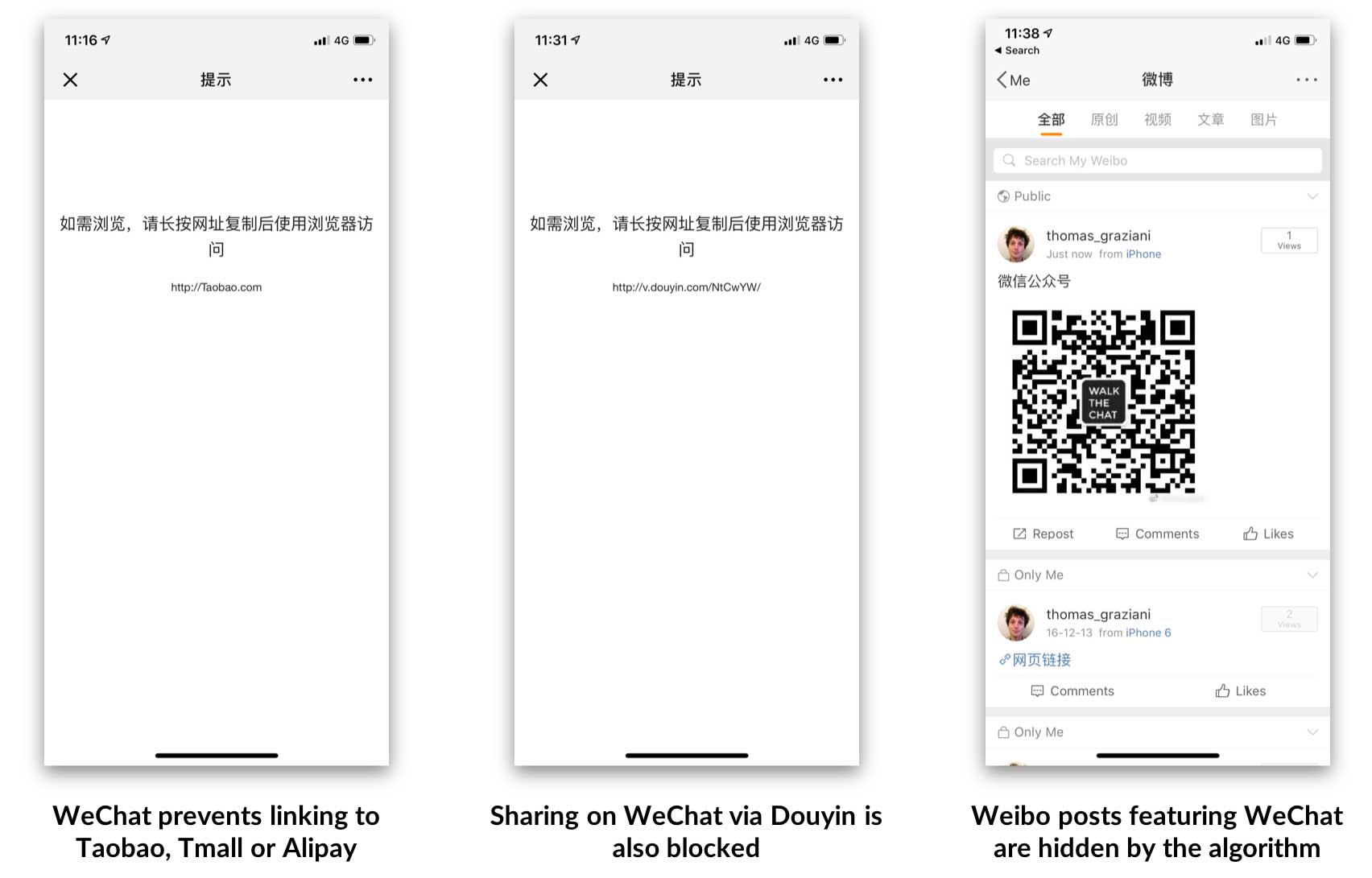

WeChat famously blocks any link to Taobao (and the other way around), while also preventing sharing from Douyin (which belongs to the competing Bytedance/Toutiao ecosystem).

Weibo (which received investment from Alibaba and is part of its ecosystem) is more subtle about blocking WeChat: posts mentioning WeChat or featuring WeChat QR codes will just receive no engagement from users as they won’t be picked by the Weibo algorithm.

The case this week of WeChat blocking the social media apps Duoshan, Duoliaotian and MatongMT is just another example of this very defensive approach to competition.

Did Facebook block competitors?

Of course Chinese tech giants are not the only companies with an history of blocking competition. A prominent example would be the case of Facebook blocking short-video platform Vine in 2013.

Photo credit: Arial Zambelich / Wired

This is however quite a different story than WeChat blocking Douyin: Facebook merely blocked the friend-finding feature from Vine (preventing it to access users contact list). Vine users were still able to share their short-videos on Facebook (which is clearly not possible between WeChat and Douyin – Douyin had to offer a workaround suggesting users to download the video and re-upload it to WeChat with a Douyin watermark).

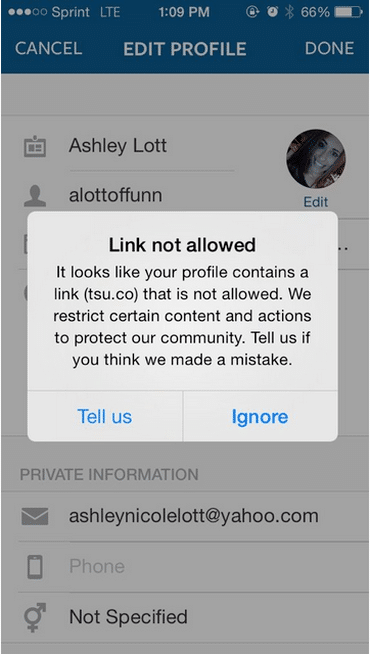

Another prominent case of Facebook blocking another competing App was the block of Tsu in 2015: a social network which was directly rewarding users for views on their content and for inviting new users.

Photo credit: zdnet.com

However, the case of Tsu is also entirely different: because it was giving money in exchange for views, Tsu was used mostly by e-marketers and spammers in order to make a quick buck. The network closed soon after, in 2016, as it failed to raise another funding round to support its apparently unsustainable business model.

A more direct case of “block” of competition happened in 2015 when Amazon decided to stop distributing Apple TV and Google Chromecast, which did not offer Amazon Prime Video streaming services. Amazon however chose to deescalate the fight last year, in December 2017, and announced that it would offer both devices again for sell on its platform.

Overall, although Western companies also can block competitors, they seem less likely to do so, and appear to do it with more focus on user experience than extinguishing their competition.

But… which strategy works best?

There is little doubt that Facebook acquisition strategy has been incredibly successful. The poster child of this success is Instagram.

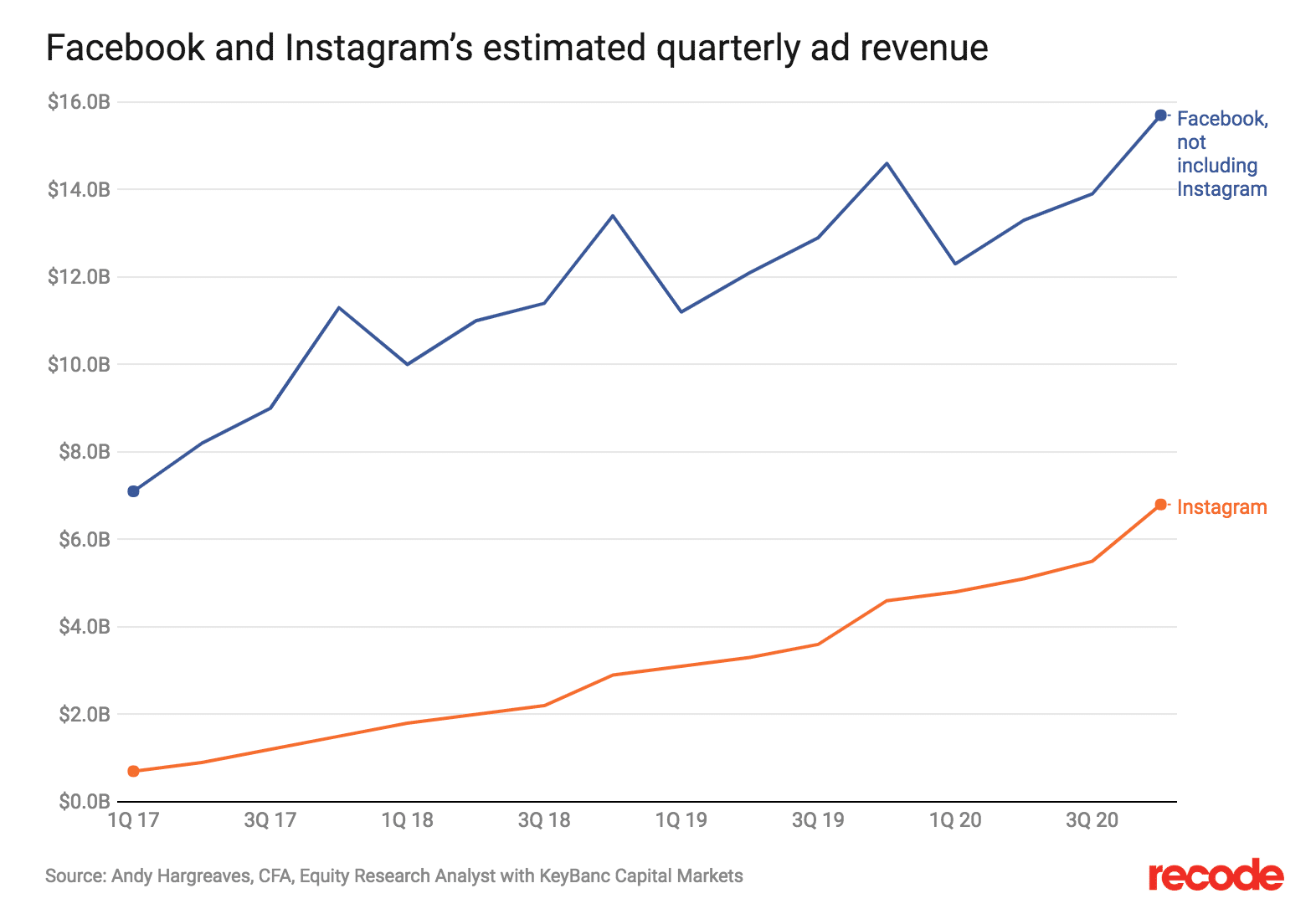

Facebook was widely criticized for overpaying for Instagram, acquired at a 1 billion USD price tag in 2012. The App is now expected to generate between 8 to 9 billion USD of revenues in 2018 alone. A pretty good return of investment, and this doesn’t take into account the strategic edge that Instagram provided against rival Snapchat.

According to Recode, Instagram could make up to 30% of Facebook total revenue by Q4 2020.

Because Chinese tech companies have a much more complex strategy of multiple, disparate investments, it is much harder to assess success. Tencent listed investees amounted to $36 billion in value as of Q2 2018, but the value of these investments goes well beyond this listing price.

As we discussed, many of such investments played into a sophisticated fight against arch-rival Alibaba and new rival ByteDance. It is likely that they contributed significantly to the rise of Tenpay / WeChat Pay, which rose from a 10% market share to around 40% in 2018 according to various estimates.

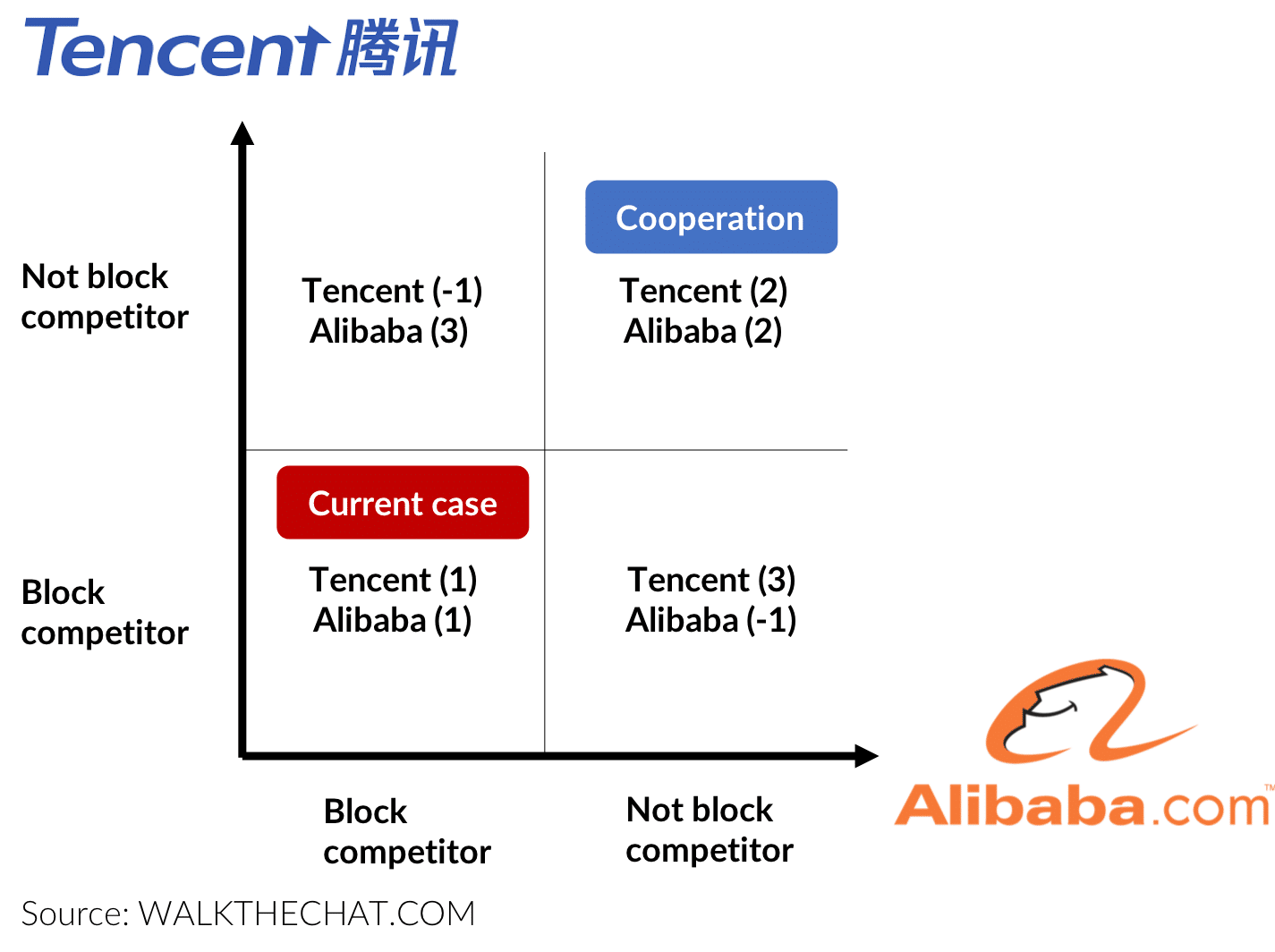

Stuck in a prisoner’s dilemma?

The habit of Chinese tech companies is reminiscent of the prisoner’s dilemma, a foundational concept of Game Theory first described by John Nash (and brought to popular culture in the movie “A Beautiful Mind”)

The prisoner’s dilemma imagines two prisoners kept in a jail. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is:

- If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves two years in prison

- If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa)

- If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve one year in prison (on the lesser charge)

This is exactly the situation that Chinese tech companies have ended up into: they can choose to cooperate and avoid damage to each other (and make a better experience for all end users). But they are so afraid of being betrayed that they end up resorting to hostile behaviors.

Of course, the math also says that, in a repeated game with reputation involved, betraying is not the only solution. At the end of the day, it is a choice that Tencent, Alibaba and ByteDance keep making every day.

Conclusion

Western and Chinese Tech companies approach competition in very different ways. As of today, it is hard to tell which way works best: Tencent, Google, Alibaba and Facebook are all incredibly successful companies with skyrocketing valuations.

One thing seems clear: these differences will likely become clearer and clearer in the future, as Chinese tech companies get entrenched in a guerrilla spreading over many industries and hundreds of invested companies.