Back a couple of years ago, WeChat seemed like an unstoppable force. It was completely dominating the Chinese social media landscape, was beating Alibaba in payments and was making forays into e-commerce.

Fast-forward to 2020, and users are already spending more time on Douyin than they are on WeChat, swiping for hours between short videos. What went wrong?

Too disruptive to be incremental

It can seem easy to pain WeChat’s current demise by their inability to spot the short-video craze early.

I would, however, argue that WeChat started losing the battle earlier. WeChat neglected incremental changes that could have improved the platform.

Back 10 years ago, Facebook would frequently revamp its interface, each time creating an uproar among its users. Yet it kept going at it, constantly refining its user experience and design.

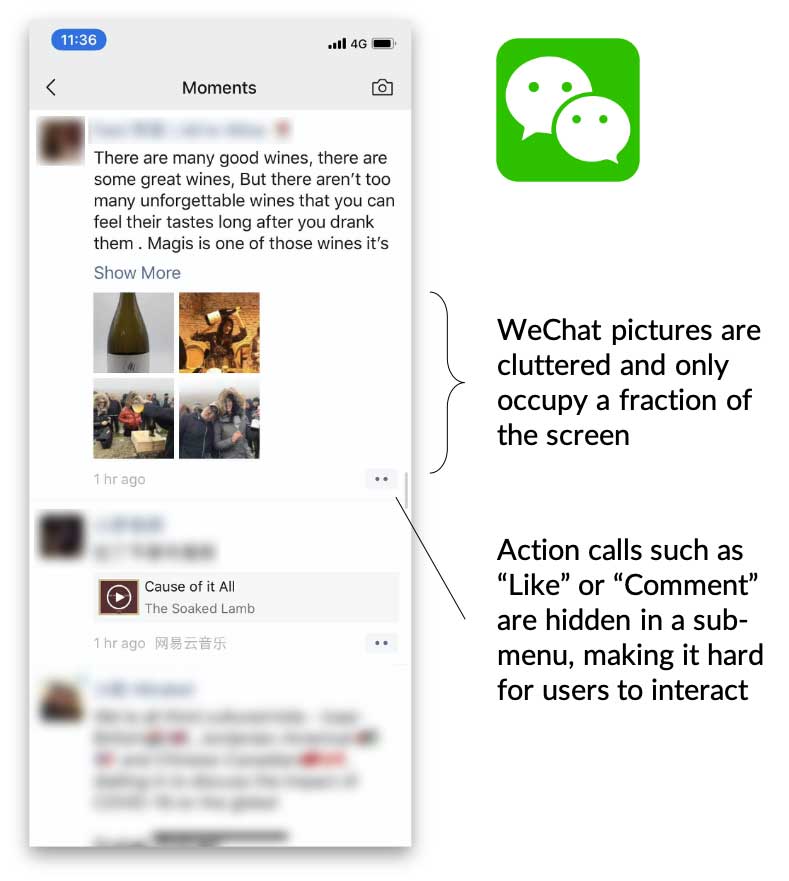

That’s something that WeChat didn’t do. The result: WeChat moments interface seems old fashioned compared to its Western competitors.

The App barely uses the phone screen, keeping pictures cluttered and forcing users to click in order to see them. Engagement buttons are also hidden in a sub-menu, making it harder for users to like photos or comments.

Facebook takes a very different approach, displaying engaging full-screen pictures and prominent actions calls to like and comment.

The truth is that WeChat has been innovating quite a bit: they launched payment, Mini-programs, and many other disruptive features that have changed the behavior of both users and businesses.

But WeChat has been looking down at small incremental changes. Tencent was apparently too afraid to make any modifications to its hit product which might anger or confuse users.

Too proud to steal

‘Good artists copy; great artists steal’. Many businessmen (such as Steve Jobs) have been shamelessly implementing this famous quote from Picasso.

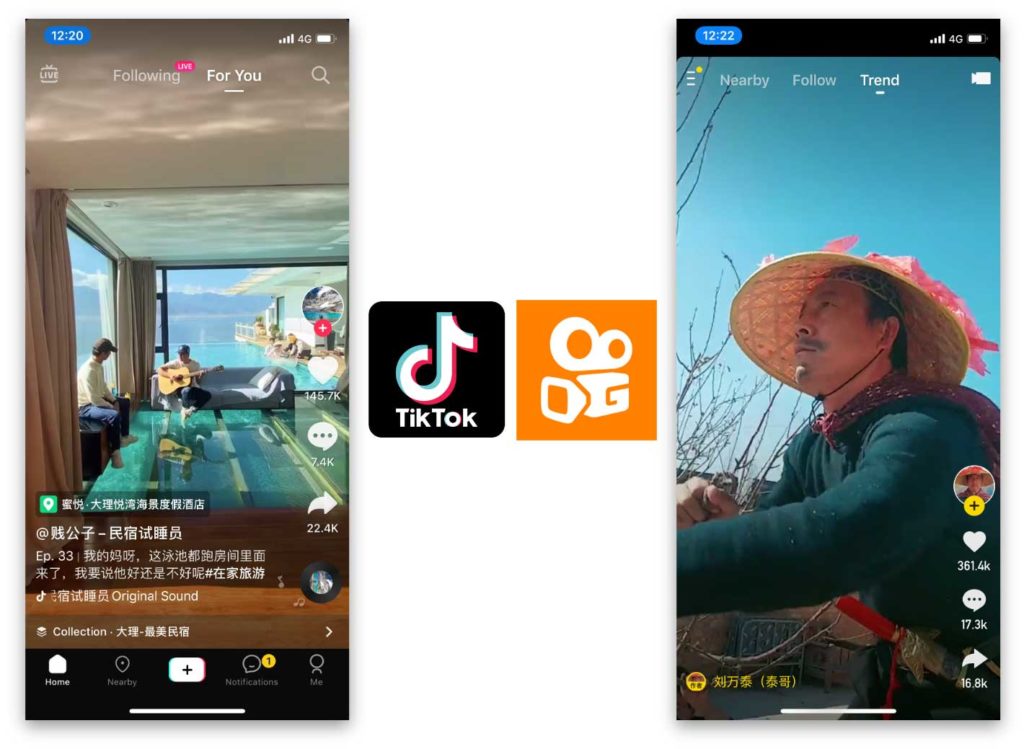

When Douyin came up with its amazingly intuitive swiping interface, that got users watching an endless stream of videos, competitor Kuaishou didn’t wait too long to copy it.

We find the same qualities of the Facebook interface: full use of the screen and prominent action calls. But most importantly: a simple swiping motion enabling to move from one video to the next.

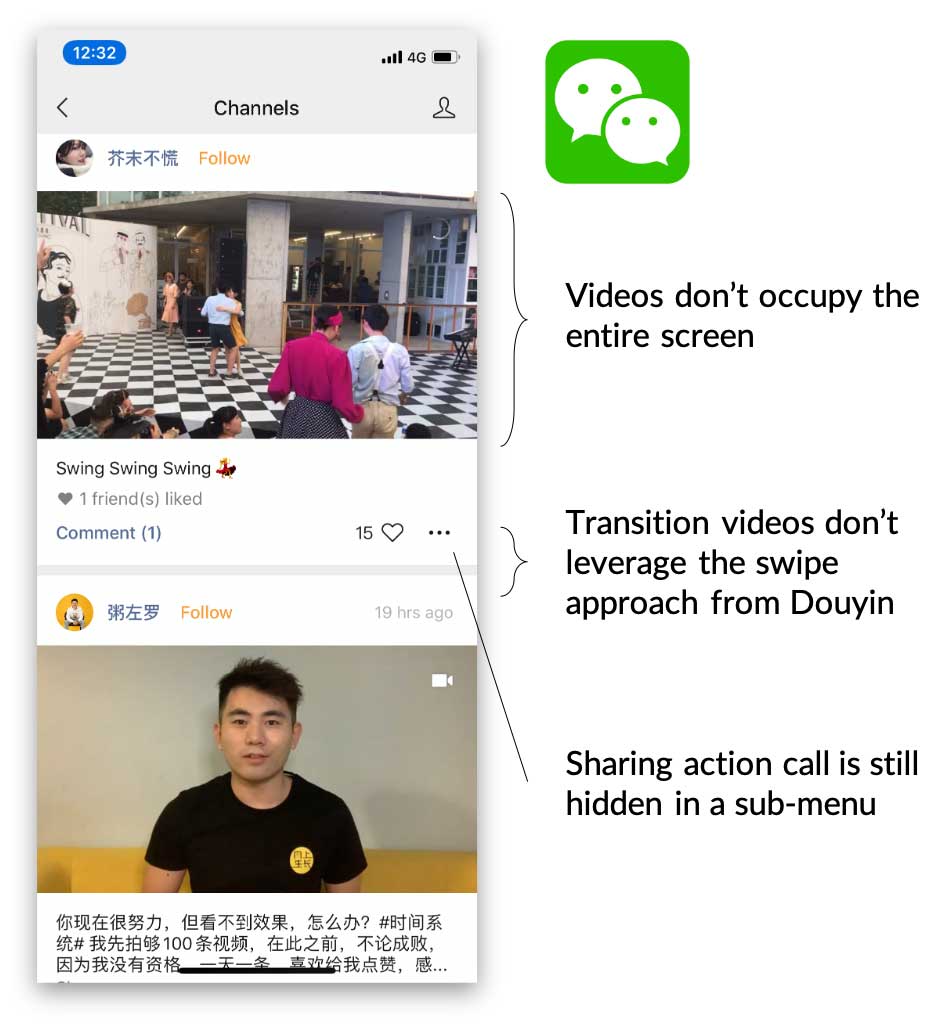

However, when WeChat released its own short-video feature, WeChat Channel, it couldn’t bring itself to copying the Douyin interface. Instead, it had to come up with its own, arguably inferior user experience.

The result is a disappointing and unengaging experience. In fact, WeChat Channels would be a great UX… for the WeChat timeline. In many ways, it looks more like the Facebook timeline than short-videos Apps such as Douyin and Kuaishou.

Too top-down to empower the masses

Another flaw of the WeChat approach is that it was and stayed a top-down content ecosystem. A few popular WeChat Official Accounts are creating the content which might become viral on the platform.

User-generated content can’t really go viral on WeChat: it is only visible to your own friends, and user-generated videos and pictures can’t easily be shared further.

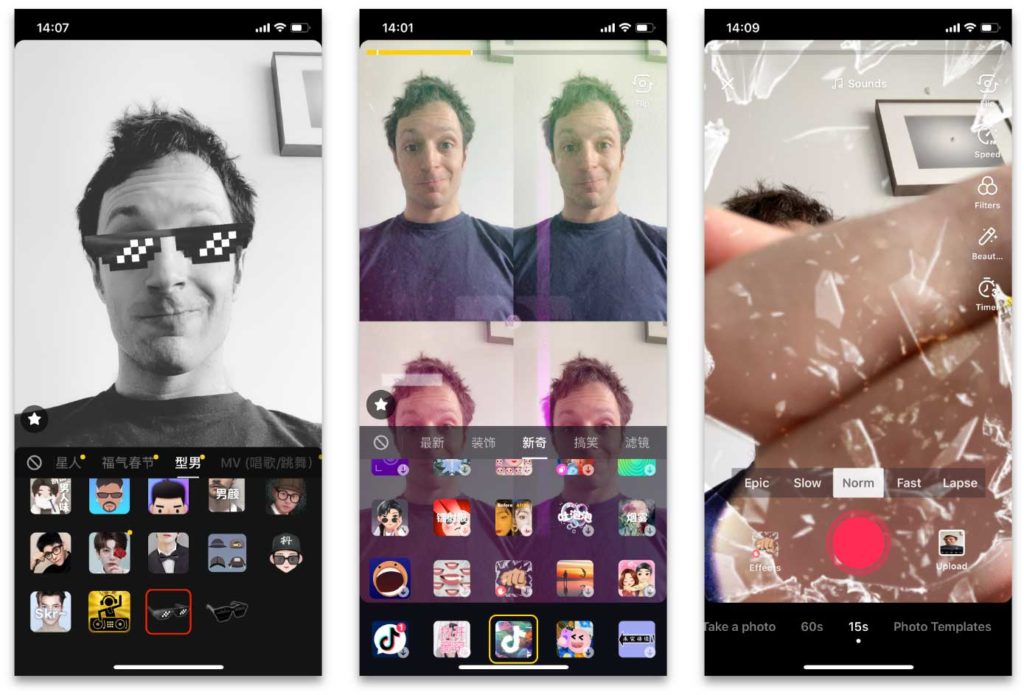

Douyin takes the opposite approach: it creates accessible tools for users to generate beautiful content. This approach was first pioneered by Instagram in the West, which helped its users generate more engaging content with filters.

This content can easily go viral, driven by Douyin’s algorithm.

In contrast, WeChat makes it difficult for users to apply for a content-creator account. WeChat Official Accounts require a special application, and creating content on them is better done on a desktop computer. Newly launched WeChat Channels also require special authorization from Tencent (although WeChat will likely simplify the application after this initial testing phase is over).

Too shy about curating content

Another drawback of WeChat is that, because it doesn’t insist on user interactions with the content (likes, comments), it also distributes content chronologically.

Almost any other modern social network takes a very different approach: Weibo, Douyin, Instagram, Facebook, and Kuaishou will all feature content which is getting the most likes and comments. Boring content that people don’t look at or interact with will be hidden for most users.

Instead, WeChat is not doing any content curation. Instead, it simply displays content chronologically on WeChat Moments. The result: you are much more likely to bump into boring food pictures than on any piece of content you would actually be interested in.

WeChat recently added a new section called “Wow” or “Top stories” in order to counterbalance this trend. Top Stories is one of the only sections that ranks content in the order of likes clicked by the user’s friends.

This shows, once again, a lack of boldness of WeChat to implement changes within its Moments section. Instead, it created a completely separate section that most users do not visit frequently.

Moreover, only 0.1% of readers of an article click “like” after reading it. Many WeChat articles take more than 5 minutes to finish reading. Thus most users won’t read to the end to click on the like button.

The fact that WeChat makes it difficult to “like” articles means there is not enough data to rank articles in the Top Story section. Very few articles reach the critical number of “likes” necessary to separate boring articles from the ones that would actually of interest (because the algorithm focuses on likes from direct friends, so the number is bound to remain small)

Conclusion: too little, too late

In the end, WeChat is doing too little and too late in order to fight off the competition from Douyin and Kuaishou.

Of course, the social network still has a lot going on for itself: it remains pretty much the only messaging platform in China. The WeChat Mini-program ecosystem is booming. WeChat Payments are stronger than ever. And some pieces of content (such as this article) are still much more suitable for WeChat than for short-video platforms.

Yet, Douyin is moving fast into Tencent territory such as gaming. There are no guarantees that it won’t move into messaging or payments.

If WeChat doesn’t react fast, it might just become another Renren.